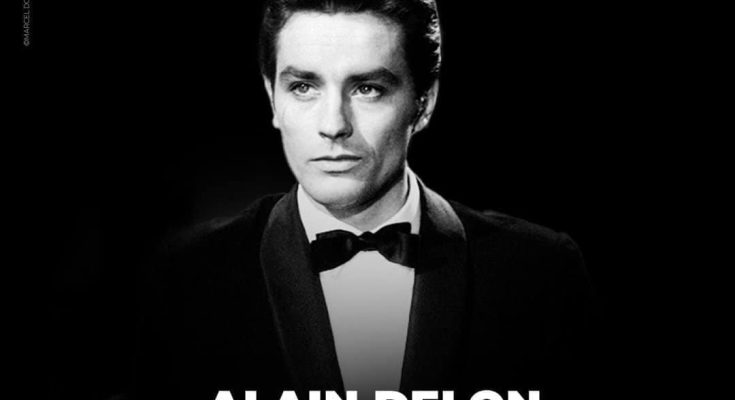

French film star Alain Delon dies aged 88

Celebrated actor and star of Plein Soleil and Le Samouraï has died, his children have said

Alain Delon, the celebrated actor who starred in a string of classic films such as Plein Soleil, Le Samouraï and Rocco and His Brothers, has died aged 88, his children have told French media.

“Alain Fabien, Anouchka, Anthony, as well as [his dog] Loubo, are deeply saddened to announce the passing of their father. He passed away peacefully in his home in Douchy, surrounded by his three children and his family,” they said in a statement, adding that the family asked for privacy.

Identified with French cinema’s resurgence in the 1960s, Delon played a string of cops, hitmen and beautifully chiselled chancers for some of the country’s greatest directors, including Jean-Pierre Melville, René Clément and Jacques Deray. He also made films with auteurs including Luchino Visconti, Louis Malle, Michelangelo Antonioni and Jean-Luc Godard – though he never quite succeeded in his attempts to make it in Hollywood.

The French president, Emmanuel Macron, wrote on X that Delon had through his acting roles “made the world dream … he offered his unforgettable face to shake our lives”.

“He was more than a star. He was a French monument,” Macron added.

Brigitte Bardot, who starred with Delon in the 1961 film Amours Célèbres, was “devastated” by his death, according to the animal protection foundation she now runs.

“Today, it is with a heavy heart we learn of Alain Delon’s death. He was an exceptional man, an unforgettable artist and a great friend to animals,” the Brigitte Bardot Foundation said in a statement.

“Alain was a close friend of our president, Brigitte Bardot, who is devastated by his death. Their friendship, based on a shared love of animals and a shared concern for their welfare, was precious and genuine. Alain understood the profound link between man and animal.” Delon, a dog lover, once said he would wish to be reincarnated as a malinois.

The French culture minister, Rachida Dati, wrote: “We believe he was immortal … his talent, his charisma, his aura made him destined for a Hollywood career at a young age, but he chose France.”

Born in 1935 in Sceaux in the Paris suburbs, Delon was expelled from several schools before leaving at 14 to work in a butcher’s shop. After a stint in the navy (during which he saw combat in France’s colonial war in Vietnam), he was dishonourably discharged in 1956 and drifted into acting. He was spotted by the Hollywood producer David O Selznick at Cannes and signed to a contract, but decided to try his luck in French cinema and made his debut with a small role in Yves Allégret’s 1957 thriller Send a Woman When the Devil Fails.

Delon’s intense good looks made an immediate impact and he swiftly graduated to lead roles. In 1958 he was cast opposite Romy Schneider in Christine. They played a soldier and a musician’s daughter who fall in love. Delon and Schneider began a high-profile real-life romance off the set, which confirmed Delon’s burgeoning reputation as a sex symbol.

In 1960 he made two films that had a significant impact internationally: the Patricia Highsmith adaptation Plein Soleil (AKA Purple Noon) and Rocco and His Brothers. The former, a French-language version of The Talented Mr Ripley, turned Delon into a major star while Rocco, a saga about a southern Italian peasant family moving to the prosperous north, brought him into the orbit of Visconti, one of Europe’s foremost auteurs. Another Italian auteur, Antonioni, cast him as a smooth-talking stockbroker in 1962’s L’Eclisse. Delon reunited with Visconti in 1963 for The Leopard (AKA Il Gattopardo), a large-scale epic set in Risorgimento Sicily, adapted from the celebrated Lampedusa novel.

Such was Delon’s international profile that he began a serious attempt to break into English-language movies, starting with a small role in the Anthony Asquith-directed anthology comedy The Yellow Rolls-Royce. Delon appeared in Lost Command, about French paratroopers in the second world war, the Dean Martin western Texas Across the River, and Is Paris Burning?, another wartime epic starring Kirk Douglas. However, none were successful enough in Hollywood to establish him there, and Delon returned to France.

In 1967 he made the cult classic Le Samouraï with the director Jean-Pierre Melville, in which he played a raincoat-wearing hitman. That film’s domestic success kicked off a string of crime films, including The Sicilian Clan alongside Jean Gabin, the Marseille-set Borsalino directed by Deray, and another Melville classic, The Red Circle. Delon also found time to appear opposite Marianne Faithfull in Girl on a Motorcycle, in which a leather-clad Faithfull rides a bike across Europe, as well as in La Piscine opposite his former lover Schneider – which was remade in 2016 as A Bigger Splash with Tilda Swinton and Ralph Fiennes.

La Piscine coincided with a huge public scandal, the “Markovic affair”, which reached into France’s highest echelons after Delon’s bodyguard Stefan Markovic was found dead in a rubbish dump in 1968. François Marcantoni, a notorious underworld figure and longtime friend of Delon’s, was charged with murder but the charges were eventually dropped. The plot thickened when compromising photos belonging to Markovic were uncovered that allegedly showed members of the French elite, including the wife of the presidential candidate Georges Pompidou. In the end nothing was proved, but Delon’s close association with a gallery of unsavoury characters became widely known.

Through the 1970s Delon continued to make films at a steady pace, without the same level of impact as in previous decades. Monsieur Klein, in which Delon played an art dealer during the second world war whose identity is confused with a Jewish fugitive of the same name, won the César for best film in 1977; in 1985 he won the best actor César for Bertrand Blier’s surreal fable Notre Histoire. Delon also branched out, producing a string of films with his own company, making his directorial debut in 1981 with Pour la Peau d’un Flic, and promoting boxing and designing furniture.

Delon began to slow his output in the 1990s after playing a double role in Jean-Luc Godard’s Nouvelle Vague. In 1997 he announced his retirement from acting, but he returned in 2008 to play Julius Caesar in the French live-action hit Asterix at the Olympic Games.

Delon had a complicated personal life, including extended relationships with Schneider, Mireille Darc (from whom he separated in 1982 after 15 years together) and Rosalie van Breemen, a Dutch model with whom he had two children and from whom he separated in 2002. He was married to Nathalie Delon from 1964 to 1968; they had one child, Anthony, in 1964. In 1962 the singer and model Nico gave birth to a son, Christian; Delon denied paternity but the child was adopted by Delon’s mother.

The former culture minister Jack Lang spoke of Delon’s kindness and their friendship of more than 20 years. Lang said Delon was “an acting giant, prodigious … a prince of the cinema”.

“He was extremely modest, reserved, restrained, shy at the same time; even if he did express himself brutally from time to time, he did it with a flourish,” Lang said.

Valérie Pécresse, the president of the Île-de-France region, wrote on X: “Goodbye dear Alain.” Éric Ciotti, the leader of Les Républicains, wrote that Delon was a star apart: “France mourns a sacred giant who existed in the daily lives of French people across the generations and who will continue to thrill us for a long time to come.”

The writer and film director Philippe Labro wrote: “Goodbye friend. A wonderful collection of films, an incredible and fascinating personality. Beauty is not enough to explain the exceptional evolution of his talent. He was the ultimate star. The Samurai.”

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you move on, I wanted to ask if you would consider supporting the Guardian’s journalism as we enter one of the most consequential news cycles of our lifetimes in 2024.

We have never been more passionate about exposing the multiplying threats to our democracy and holding power to account in America. In the heat of a tumultuous presidential race, with the threat of a more extreme second Trump presidency looming, there is an urgent need for free, trustworthy journalism that foregrounds the stakes of November’s election for our country and planet.

Yet, from Elon Musk to the Murdochs, a small number of billionaire owners have a powerful hold on so much of the information that reaches the public about what’s happening in the world. The Guardian is different. We have no billionaire owner or shareholders to consider. Our journalism is produced to serve the public interest – not profit motives.

And we avoid the trap that befalls much US media: the tendency, born of a desire to please all sides, to engage in false equivalence in the name of neutrality. We always strive to be fair. But sometimes that means calling out the lies of powerful people and institutions – and making clear how misinformation and demagoguery can damage democracy.

From threats to election integrity, to the spiraling climate crisis, to complex foreign conflicts, our journalists contextualize, investigate and illuminate the critical stories of our time. As a global news organization with a robust US reporting staff, we’re able to provide a fresh, outsider perspective – one so often missing in the American media bubble.

Around the world, readers can access the Guardian’s paywall-free journalism because of our unique reader-supported model. That’s because of people like you. Our readers keep us independent, beholden to no outside influence and accessible to everyone – whether they can afford to pay for news, or not.

If you can, please consider supporting us just once, or better yet, support us every month with a little more. Thank you.

Thank you for sharing such valuable information!